Announcements

Welcome to Potions 501!

Please read the following announcements before joining the course.

1. If you have submitted an assignment for this course, do NOT send the grading staff a message asking when your work will be graded if less than a month has elapsed. If more than a month has elapsed, please contact Professor Draekon and provide your Grade ID for that assignment in your message.

2. If you have any questions about the course content, please reach out to any Professor's Assistant for Potions 501. A list of current PAs can be found on the right side of this page.

3. If you believe an assignment has been graded in error, please reach out to Professor Draekon or Andromeda Cyreus, and provide your Grade ID for that assignment in your message.

4. Suggestions, compliments and constructive criticism about the course are always appreciated. If you have any comments about Potions 501, please send an owl to Professor Draekon.

Lesson 3) Happiness and Hedonic Treadmill

There is a feeling in the air that makes the oppressive dungeons seem, somehow, more welcoming today. The atmosphere of the room, usually somber and heavy, feels more relaxed, and you notice that people are talking in louder voices before class starts. Intrigued, you scan the room for anything that might help explain why people are more at ease - until you find an uncorked pitch-black vial atop the front table. You move closer, peering into the container and seeing a yellow brew that seems to be bursting with energy. A soft glow emanates from the liquid, and you can almost feel as if you were outside, sensing the heat of the sun touching your skin.

Suddenly, you hear heavy steps making their way into the classroom, causing your daydream to fade away. The familiar tall man takes his place in front of the classroom, leaning against his desk right next to the potion. “I assume you are all excited for a more lively topic today. Without further ado, let us get right into it.”

Biological Definition of Happiness

I would like to start today’s class by discussing happiness. Despite the fact that feeling happiness on a personal level might be quite instinctive for us, defining happiness can be a quite daunting task, particularly when what makes us happy might vary from person to person. One might feel happiness at the prospect of talking to a new person, whereas others might completely dread the experience.

I would like to start today’s class by discussing happiness. Despite the fact that feeling happiness on a personal level might be quite instinctive for us, defining happiness can be a quite daunting task, particularly when what makes us happy might vary from person to person. One might feel happiness at the prospect of talking to a new person, whereas others might completely dread the experience.

I usually do not indulge in personal anecdotes in class, but I feel like there’s an example that could illustrate what I mean. If you’d all recall my background, I was born in Japan - a country that is home to a writing system that is very different from the one used in Western culture, mostly due to the fact it contains thousands of characters that can be conjugated in order to create new words and phrases. Most of my friends dreaded learning about Kanji - the aforementioned writing system and its characters - in school, while I was particularly content in studying them on my own. Although this might seem unrelated to Potions at a first sight, there are strong parallels between Kanji and potioneering: both systems contain a plethora of tools that can be mixed and matched in new ways, but the final product will, more often than not, have a very strong relation to the base ingredients that you used.

Let us get back on track. The previous discussion indicates that happiness, as a psychological construct, is largely subjective - that is to say, it will vary based on who you are as a person. Many philosophers and celebrities have tried to find a suitable definition for happiness, ranging from “what you think, what you say and what you do in harmony” (Gandhi) to “enjoying the present, without anxious dependence upon the future” (Seneca).

Although there is value to discussing such subjective definitions in other classes, this debate is of little help when it comes to Potions. In fact, some scientists are quite vocal in stating that happiness, from a perceptual standpoint, is an empty term - Martin Seligman states that he “actually detest[s] the word happiness, which is so overused that it has become almost meaningless” and that it is “an unworkable term for science”.

Nevertheless, the latter point can, and will, be logically criticized. It is true that happiness can take on a myriad of forms, but the biological phenomena that occur in the human body are quite similar between humans, regardless of the source that causes the feeling of happiness in the target individual. Therefore, it is reasonable to surmise that happiness can be defined from a biological standpoint in addition to a subjective one - the latter discussing what makes humans happy, whereas the former simply focuses on how humans come to experience that happiness.

From a biological standpoint, happiness is the overall pleasant feeling generated by high levels of specific neurotransmitters - more specifically, serotonin, dopamine, endorphins and oxytocin. We shall cover the concept of a “neurotransmitter” in greater detail later on; still, for the time being, you can consider a neurotransmitter as a messenger of sorts.

Very well. If neurotransmitters are equivalent to messengers, what kind of messages are mediated by the neurotransmitters related to happiness? In order to understand that, we must dive deeper into the fundamentals of evolution.

Evolutionary Role of Happiness

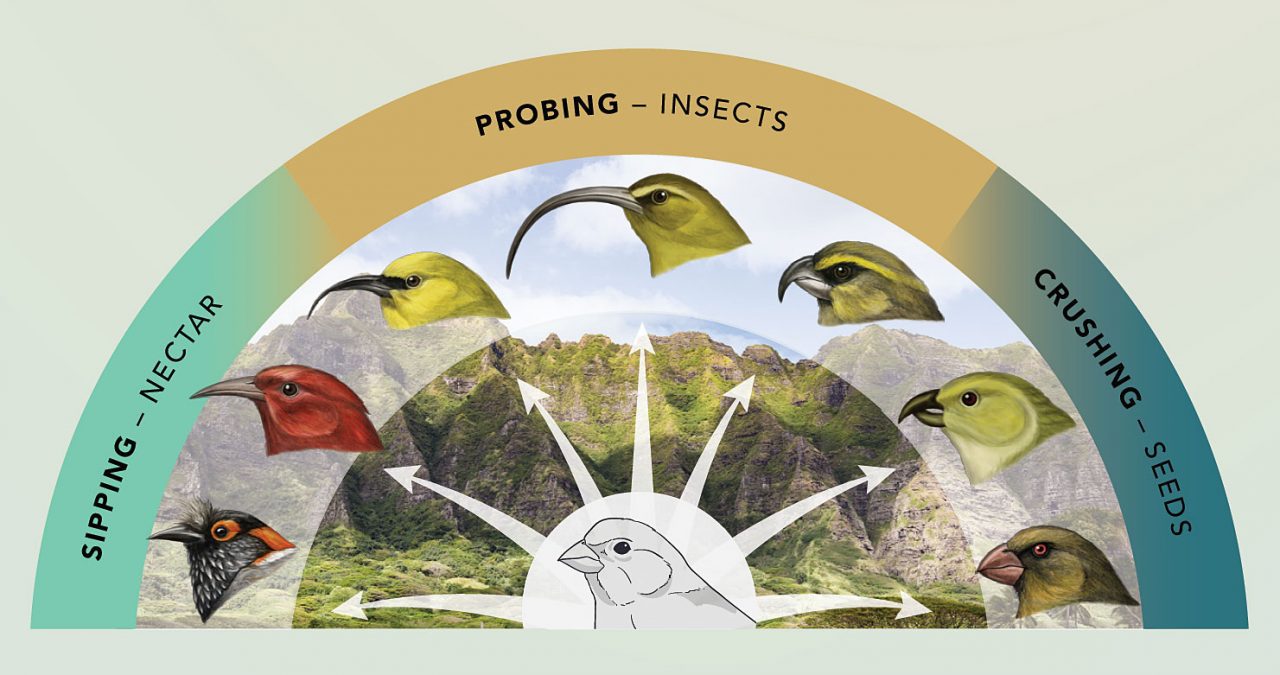

Some of you might be familiar with Evolution Theory, even if just in passing. This theory, proposed by Charles Darwin in 1859, states that the individuals who are best adapted to a specific set of challenging circumstances - also called “evolutionary pressures” - pass their genes forward, while those who are poorly adapted die in the long run. These evolutionary pressures create a so-called “natural selection” through which the most suitable specimens thrive - hence, why evolution is frequently summarized by the expression “survival of the fittest”. Do note, however, that fittest does not always mean “strongest” - for example, an animal with a dainty body can be the fittest to survive in an environment where food is scarce.

Understanding this concept is easier with a given example. Let us assume that a specific bird has a given gene (‘A’ or ‘a’), which determines whether the bird can safely consume a specific chemical present in coffee beans. If the bird has a gene ‘A’, it can safely consume coffee beans; however, if the bird has version ‘a’ of the gene, it will have a negative reaction to coffee beans.

Understanding this concept is easier with a given example. Let us assume that a specific bird has a given gene (‘A’ or ‘a’), which determines whether the bird can safely consume a specific chemical present in coffee beans. If the bird has a gene ‘A’, it can safely consume coffee beans; however, if the bird has version ‘a’ of the gene, it will have a negative reaction to coffee beans.

Let’s assume that we start with equal numbers of ‘A-birds’ and ‘a-birds’ who live on an island where coffee beans are the only source of food. As time goes by, the a-birds will have negative reactions from eating coffee beans - thus, becoming sick more easily and, in severe cases, even dying from the toxicity of the chemical contained in coffee. Conversely, the A-birds will not experience the same effect, living normally.

In the provided example, which of the bird types is more likely to die early without passing its genes forward, and which of the bird types is more adapted to the food sources present in the island? Since the A-birds are more adapted to the environment, this means that they are more likely to reproduce and have children, who will also have a copy of the ‘A’ gene. As new generations are born, it is expected that most of the birds in the island will be A-birds, with a minority belonging to the a-bird type.

I would like to address two particular misconceptions of evolution at the present time. First of all, evolution does not mean “one animal becomes another as time goes by”, as some people tend to believe; rather, it implies a series of adaptations in reaction to environmental pressures.

The second issue I would like to address is the misconception that “humans evolved from monkeys”. This simplification, albeit instinctive for a child who can see the resemblances between man and animal, is quite mistaken. Rather, both humans and monkeys evolved from a common ancestor, which adapted in different ways to the surrounding environment: monkeys adapted by becoming skilled in climbing, whereas humans adapted by learning how to use simple tools.

In order to drive these points forward for a last time, allow me to provide yet another analogy. One can think of evolution as a school of sorts, which prepares us for having a job in the real world. There is no particular job that is best suited for living, although there are plenty of requirements for you to be successful in a given job. Small adaptations on how jobs are done are possible given enough time (one can compare how modern potioneering differs from ancient potions, for example), but a given job will never become a completely different one.

If we were to map the elements of the previous analogy onto life, we would get a quite a comprehensive overview of evolution. All creatures came from a common ancestor (“person before school education”), which became adapted to life in a given way (“different jobs in real life”). There is no particular adaptation to life that can be considered “best”: both humans, who rely on tools and intellect, and bacteria, who rely on their ability to multiply quickly, found a way through which they could continue living. We might see small changes in creatures as time passes by (for example, humans in Africa are dark-skinned as an adaptation to the sunlight levels present in the area), but humans will never become another creature, nor will other creatures ever become human.

Having said that, what is the relation between happiness and evolution? In order to answer the question, let us consider what makes humans happy or unhappy as a whole. There are a few situations that are regarded as largely pleasant or unpleasant, regardless of your background: for example, eating good food is usually connected to feelings of happiness, whereas being hurt is usually connected to personal dissatisfaction.

Therefore, we can deduce that happiness is a tool that was developed over time, incentivizing us to act in ways that helped us live and avoid behaviors that could lead to our death. Those who got a “chemical reward” for doing self-preserving behavior became better adapted to life, and this is why happiness is strongly linked to human evolution.

The task of abridging Evolution Theory in a single lecture chapter is no easy task, and there were several corners that I had to cut throughout my explanation. In case the topic interests you, do note that my owl post is always open for further discussion and/or clarifications.

Biochemistry of Neurotransmitters

(Full size image accessible HERE.)

I have stated that neurotransmitters are messengers of sorts in the human body - however, it is time to expand on that definition in order to get a better picture of how these “messengers” operate in our bodies.

We have discussed that every aspect of our body is mediated by our nervous system in this year’s first lesson, including our heartbeats, our breathing, our body movements and our physical sensations (such as cold and pain). However, a complex network of neurons is involved throughout the process, and as such these neurons need a way to coordinate with one another.

Let us consider a specific process, such as a heartbeat, as an example. In order to beat properly, specific parts of the heart must contract and relax in a specific rhythm and pattern: initially, the muscles of the heart relax to receive blood in its entrance, followed by a coordinated contraction of the muscles close to the entrance and relaxation of the muscles close to the exit so the blood will move closer to the “ejection area”. Last, the valves to the entrance areas are closed and the muscles close to the exit contract, forcing the blood to flow out of the heart and through the body.

As you can see, this process requires multiple smaller steps that must be synchronized with one another for the heart to beat properly. In order to achieve that effect, a specific neurotransmitter called acetylcholine tells each nerve in charge of the heart muscles when and how to move, creating a smooth heartbeat.

There are three main categories of neurotransmitters - namely, excitatory, inhibitory or modulatory. Excitatory neurotransmitters make neurons fire more easily, becoming more “sensitive” to triggers; incidentally, the production of excitatory neurotransmitters is why ingesting sugar makes some children hyperactive and restless.

Conversely, inhibitory neurotransmitters decrease how frequently neurons fire, diminishing a person’s reaction to external stimuli. One apt example of an inhibitory neurotransmitter is GABA, which is strongly associated with relaxation and sleep; the production of GABA is the main reason why people who drink alcoholic beverages become sluggish and relaxed.

Last, but not least, modulatory neurotransmitters are involved in the coordination of different neurons and/or neurotransmitters. Rather than making a neuron more or less likely to send a signal, a modulatory neurotransmitter acts as a manager for a specific group, ensuring they all operate as a cohesive unit.

These neurotransmitters can then work in tandem, creating a combined effect that derives characteristics from each neurotransmitter involved. In the table above, you can see that multiple neurotransmitters have been listed, each one with its specific role. Whenever we feel happiness, what we are actually experiencing from a biological standpoint is a combination of serotonin, dopamine, endorphins and oxytocin, which all contribute to the final overall sensation. At the risk of overusing the analogy, neurotransmitters too are quite similar to potion ingredients: they are essential units that can be used to create larger effects when paired with one another.

Tolerance and Hedonic Treadmill

Before we finally discuss today’s potion, I would like to discuss a few more concepts related to our body’s biochemistry and psychology. First, let us start with tolerance, or how the body chemically adapts to external stimuli with time.

You may remember the fact that some recipes of the past stated that some brews - such as specific types of Sleeping Draught - are habit-forming, but what does that mean? In a nutshell, a substance is considered habit-forming when using the brew causes the body to adapt to it, requiring larger and larger doses of the potion to obtain the same result. This process of body adaptation is called “tolerance”, as the body begins to tolerate greater amounts of the target chemical due to exposure to it.

A good example of a habit-forming substance is cocaine, which is an illicit Muggle stimulant. The consumption of cocaine causes a huge spike in a person’s dopamine and serotonin levels, causing an immediate sensation of pleasure. However, this “high” is also associated with a very dangerous consequence: the human body is not adapted to function with these extremely high levels of neurotransmitters, and as such the body of an individual who consumes cocaine will gradually “kill” some of the neuron regions that communicate with the serotonin and dopamine molecules.

It is the killing of these regions that cause tolerance and habit-forming. After the death of these binding sites, a normal level of serotonin and dopamine is perceived as “too low” for the body, since that person’s neurons have fewer regions that can receive these neurotransmitters when compared to a normal body. In other words, the person must now keep on consuming cocaine (thus elevating the amount of dopamine and serotonin in their blood) to feel like a normal person does, creating a permanent or semi-permanent cycle in which higher and higher doses of the stimulant are required for a person to feel normal again. This is the vicious cycle that leads to chemical addiction and the reason why I strongly urge you to never be roped into taking any type of drug.

I cannot emphasize this strongly enough. If you were to take only one thing from today’s lecture, this is the lesson I want to impart: do not fall into the temptation of trying any type of illegal drug, as there are several dangers (both from a biological and from a legal standpoint) associated with the practice. Many people plan to take an illegal stimulant just to “try it out” and suddenly see themselves in a hole that is far too difficult to escape from.

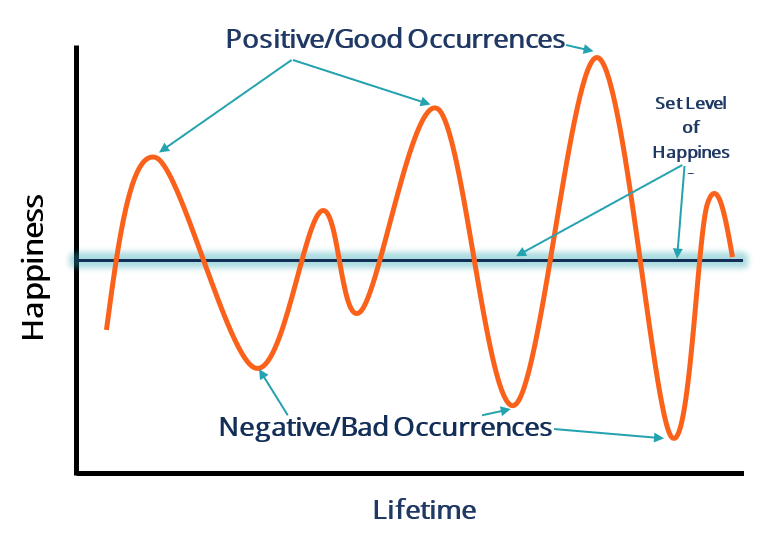

Very well. In a similar way to how our bodies can acquire physical tolerance to certain chemicals, we can also become psychologically tolerant to external stimuli, adapting to happiness and sadness as it becomes our new “standard”. This phenomenon too has a technical name - it is called the “hedonic treadmill”, and it illustrates how we usually converge to a baseline level of happiness. Frequently we think that we will be extremely happy if we enter the job of our dreams or get married to the one we love - and, although this is true at first, we tend to adapt to these fortunate or unfortunate events after a while.

Very well. In a similar way to how our bodies can acquire physical tolerance to certain chemicals, we can also become psychologically tolerant to external stimuli, adapting to happiness and sadness as it becomes our new “standard”. This phenomenon too has a technical name - it is called the “hedonic treadmill”, and it illustrates how we usually converge to a baseline level of happiness. Frequently we think that we will be extremely happy if we enter the job of our dreams or get married to the one we love - and, although this is true at first, we tend to adapt to these fortunate or unfortunate events after a while.

This is neither positive nor negative; rather, the hedonic treadmill simply indicates that there’s no happiness that is eternal, nor any sadness that lasts forever. However, our adaptation to a certain standard of happiness means that removing what we got used to might lead us to temporary unhappiness. Think of a divorce, for example: if we come to take the company of a person for granted, suddenly losing the presence of this individual can make us feel sad until we get used to this new reality.

The Elixir to Induce Euphoria, which we will begin brewing in a moment, does not induce tolerance - that is to say, it does not cause chemical changes in the body that force us to adapt to the presence of the potion in our bloodstream. However, there are strong psychological effects associated with taking the Elixir to Induce Euphoria as described by the hedonic treadmill phenomenon, and for that reason taking the potion too frequently is not encouraged.

Elixir to Induce Euphoria

Estimated Brewing Time:

Pewter Cauldron: 1 hour, 53 minutes and 10 seconds

Brass Cauldron: 1 hour, 42 minutes and 16 seconds

Copper Cauldron: 1 hour, 32 minutes and 27.4 seconds

Ingredients:

1 L of water

2 Shrivelfigs1

19 g of crushed porcupine quills1

3 Sopophorous beans1

1 sprig of peppermint2

10 drops of wormwood infusion2

50 mL of rose water3

Instructions

Part One:

1. With the heat still off, add 1 L of water to your cauldron.

2. Bring the heat to 446 Kelvin (172.85°C/343.13°F).

3. Cut both of your Shrivelfigs in half, then squeeze the contents of one of the halves into the cauldron. Do not add the skin of the Shrivelfig half to the cauldron.

4. Stir the contents of your cauldron twice counterclockwise.

5. Add 19 g of crushed porcupine quills to the skin of the Shrivelfig whose contents was squeezed out.

6. Macerate the Shrivelfig skin containing the crushed porcupine quills with the side of your knife until you obtain a paste-like consistency, then add the produced paste to your cauldron.

7. Add two of the remaining three Shrivelfig halves to your cauldron, then stir its contents counterclockwise until your potion turns navy blue. Three to four stirs are usually required for this step.

8. Bring the heat to 391 Kelvin (117.85°C/244.13°F) and let the potion simmer in your pewter cauldron for 32 minutes.

(This would be 28 minutes and 48 seconds in a brass cauldron and 25 minutes and 55.2 seconds in a copper cauldron.)

At this point, your potion will be mauve-colored and smell like chestnut. An oily sheen should cover the surface of the potion, reflecting any type of light that is not green.

Part Two:

1. Bring the heat to 313 Kelvin (39.85°C/103.73°F).

2. Add the peppermint sprig to your cauldron, then stir its contents three times clockwise. The potion must release a puff of red smoke immediately after the peppermint sprig is added; otherwise, discard the potion and start anew. Brews that do not release the puff of red smoke are associated with uncontrollable fits of laughter that lead to asphyxiation if untreated.

3. Squeeze the juice of 3 Sopophorous beans in a separate vessel, then combine the produced juice with 50 mL of rose water.

4. Mix the Sopophorous bean juice and the rose water with a wooden spoon until the mixture begins to froth slightly.

5. Add the Sopophorous bean juice and rose water mixture to your cauldron, then stir its contents once clockwise.

6. Bring the heat to 556 Kelvin (282.85°C/541.13°F) for 1 minute regardless of cauldron, then lower the heat to 404 Kelvin (130.85°C/267.53°F) and let the potion simmer in your pewter cauldron for 28 minutes.

(This would be 25 minutes and 12 seconds in a brass cauldron and 22 minutes and 40.8 seconds in a copper cauldron.)

At this point, your potion should be a murky brown and smell faintly like black mold. A small whirlpool will spontaneously be formed in the liquid every minute.

Part Three:

1. Bring the heat to 379 Kelvin (105.85°C/222.53°F).

2. Gradually squeeze the contents of the remaining Shrivelfig half into your cauldron until the brew turns hot pink.

3. As soon as the potion changes color, immediately add the remaining Shrivelfig skin to your cauldron, then stir its contents counterclockwise five times or until the potion turns orange, whichever comes first.

(Note: To clarify, this means that you are going to stir the potion five times if it does not turn orange, or fewer times if it turns orange while stirring.)

4. If your potion did not turn orange in the previous step, cast a Cheering Charm directed at the brew. If the potion does not turn orange after this step, start anew.

5. Gradually add the 10 drops of wormwood infusion to your cauldron at a rate of 1 drop every 19 seconds.

6. Bring the heat to 338 Kelvin (64.85°C/148.73°F), then let the potion simmer in your pewter cauldron for 49 minutes.

(This would be 44 minutes and 6 seconds in a brass cauldron and 39 minutes and 41.4 seconds in a copper cauldron.)

7. Immediately siphon the potion into its appropriate vial. No maturation or cooling times are required.

The final potion will be a vivid yellow and emit some rays of sunlight if brewed properly. It smells like fresh rain hitting the ground and tastes quite similarly to a custard pie.

Storage:

Store the Elixir to Induce Euphoria in a pitch-black container. The potion can tolerate any temperature between 0°C and 40°C, and as such no specific considerations must be done for the container’s temperature. The potion’s expiration date is directly correlated to how much has been used from the vial - a full vial takes approximately one year to expire, whereas the contents of a half vial expire in six months.

This leads to some interesting scenarios in which an unexpired potion might expire instantly. For example, if you have stored the Elixir to Induce Euphoria for ten months and suddenly use half of the content in your vial, the remaining half in the vessel will expire as soon as you stop pouring the liquid. Nevertheless, any amount of Elixir to Induce Euphoria added to a beverage will not follow the same rule - after adding the brew to another drink, you may consume the mixed beverage within 15 minutes for full effect.

Usage:

Pour 5 to 20 mL of the Elixir to Induce Euphoria into your favourite non-alcoholic drink, then consume the mixture in the next 15 minutes. You should feel contentedness immediately upon drinking the brew.

Caution:

Do not consume this version of the Elixir to Induce Euphoria on its own, as its effects are more concentrated than most other versions of the same potion. Some side-effects, such as excessive singing and nose-tweaking, are associated with the potion in some cases, particularly when larger doses are taken. If you have any type of negative reaction, discontinue use immediately and seek healer attention.

Closing

As you may have noticed, the notes on the brew I provided today explicitly mention “this version of the Elixir to Induce Euphoria”. Although we assumed, for every potion we have studied so far in this course, that there is only one way to brew them properly, this is far from the truth. Particularly in the case of the Elixir to Induce Euphoria, there are several recipes that are tried and tested: some of them add the peppermint sprig in the beginning of the process, whereas others include the sprig in the middle or even not at all. Some recipes use castor beans instead of Sopophorous beans. Some recipes call for the use of the Cheering Charm regardless of how the ingredients react with one another. These are a few examples that illustrate how varied brewing can be, especially in potions that have been extensively researched.

Naturally so, each set of instructions comes with its advantages and disadvantages. In a sense, we can equate potioneering to cooking - there are multiple ways through which we can make a specific dish, such as a pecan pie, but some basic principles must be kept in place for our “recipe” to be considered an authentic pecan pie. Until you understand these principles on an instinctive level, I do urge you to keep to the instructions provided by reputable sources; you will have plenty of time to dabble in experimental potioneering if you proceed with your N.E.W.T.s in Potions.

Dismissed.

Original lesson written by Professor Vaylen Draekon

Image credits here, here, here and here

- PTNS-401

Enroll

-

Get Excited

Quiz -

Transmission Complete

Essay -

Closing The Bridge

Essay -

Potions, Year Two Theory

Test

-

Andromeda Cyreus

Head Student