Lesson 1) Journey to Japan

The classroom looks a little starker than usual. While the stone walls are still far from unadorned, the aristocratic silk wall hangings are few and far between, almost as if to draw more attention to them. On the desk in the front of the class, there is a strange dichotomy of objects: many small items and a mirror that looks like it might be part of a vanity, and a prominent samurai helmet.

The click of heels on hard stone announces the professor’s arrival, but as some students turn in their seats, they notice that it is only Professor Wessex. Professor Morgan is nowhere in sight, in contrast to their dual introduction last year. The petite professor clears her throat and begins the class without further delay.

Introduction

Hello, students. Welcome to this, your final year of Mythology. You may have noticed Professor Morgan’s absence. Unlike last year, I alone will be teaching the Seventh Year of this course. As those of you who have taken Ancient Runes will know, Asia is my area of expertise, and Professor Morgan and I have arranged for me to finish your N.E.W.T. level studies with this area’s mythology.

In the interest of clarity, there will be no changes to the normal administrative pieces. The rubric will still be the same setup: 80% content, and 20% divided between spelling and grammar as well as word count and identifying marks. More specific rubrics will be available for individual assignments. As before, you will also be required to do a fair amount of critical thinking about the information in the lesson, not simple regurgitation of facts.

There will be a N.E.W.T. for this course, despite the fact that there was not an O.W.L. in Year Five. I am sure you have vivid memories of your O.W.L.s from other classes, but unfortunately, you will not have a benchmark for Mythology. If you are concerned about this, there will be optional review assignments throughout the year, including a mock N.E.W.T. exam in two parts towards the middle of the year, which will prepare you more than adequately.

A Guideway Through Mountains and Seas

On the topic of assignments upcoming this year, it’s time for a look at the curriculum. We will be filling in the rest of the gaps in your education with a look at Asia and Oceania. From your discussion of these regions in Ancient Runes and History of Magic, you will know that this is no small feat. This area is quite expansive and varied, housing the largest number of countries in comparison to all other continents. Our content this year will be a whirlwind tour through as many key countries and their myths as possible. You can get a general idea of our topics in the syllabus here.

As another technical note, when convenient, I will attempt to mention overlap on other courses, such as Year Four History of Magic, as well as Year Six of Ancient Runes and Ancient Studies, but I cannot guarantee that I will mention them at all applicable times. Therefore a background in all of those courses is highly recommended and advantageous.

Ancient Japanese Matters

Without further ado, we must jump immediately into our discussion of Japan today. To say we’re studying Japanese mythology is actually an oversimplification. There are many cultural groups in Japan that contribute to their legends and folklore. Most notably there are Buddhist traditions, Shinto, and Oomoto myths, and more localized regional folklore. Of course, there are some traditions (such as reverence of ancestors, worship at shrines, etc.) that are shared generally across most of the population. We will take a brief look at all of these categories in class today, starting first with the most general topics.

General

Two books of great importance to the overall mythological traditions of Japan are the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki. These books record the legends, folklore, and in some cases the history of the country, itspeople, its creatures, and the royal family. The first, which translates to “Records of Ancient Matters,” was recorded in the early 8th century, around 711 B.C.E. and contains myths, songs, and genealogies. The topics covered range from the beginnings of the imperial family and the islands of Japan themselves, as well as myths about the kami (or spirit gods). The Nihon Shoki is much the same. Also called the Nihongi, which translates to “The Chronicles of Japan,” it was finished later than the Kojiki, in 720 B.C.E., and is more detailed. However, it contains generally the same topics and information.

While these books are important, they do not hold a candle to a third book — the Hotsuma Tsutae. It is not nearly as famous as the other two books, but it is believed by the majority of magical scholars to be more accurate and to have been written predominantly or solely by witches and wizards. Technically speaking, this is no guarantee that it’s more accurate, as ancient magical books and myths easily become warped from misunderstandings and retellings over the ages, or may have been told to authors via second or third hand accounts. However, it holds significantly more weight in the magical community.1 That doesn’t mean we should discount the information in either the Kojiki or the Nihon Shoki, but to view them with a grain of salt.

this is no guarantee that it’s more accurate, as ancient magical books and myths easily become warped from misunderstandings and retellings over the ages, or may have been told to authors via second or third hand accounts. However, it holds significantly more weight in the magical community.1 That doesn’t mean we should discount the information in either the Kojiki or the Nihon Shoki, but to view them with a grain of salt.

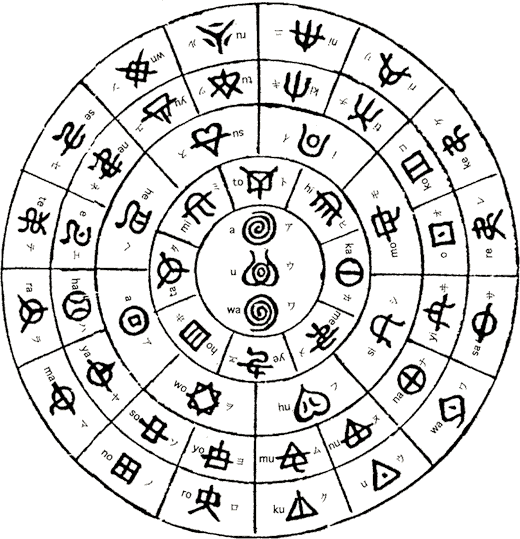

These beliefs about the origins of the books stem from the fact that the contents of the Hotsuma Tsutae are radically different from the other two. Contained within, there is a chart detailing a guide to divination using the Hotsuma symbols. Instead of detailing the lives of the many emperors and empresses, it contains mostly myths, typically telling of magical or pseudo-magical events, the most notable of which we will examine later in the lesson. Finally, it was also written in a script known as Hotsuma (or Woshite) that was used prominently for magical purposes around nearby shrines.

The Beginning of Time

In the aforementioned books, the creation of heaven and earth is detailed. The myth opens with chaos, and describes different substances such as particles and light. The light rose highest and formed the top of the universe, with the heavier particles below it, which made the clouds and the heavens. All the heaviest bits, which were not able to rise at all, formed the earth as we know it. At the same time, the first gods, or kami, appeared on Earth. The three of them were called Amenominakanushi, Taka-mi-mushi-no-kami, and Kami-mushi-no-kami. At the same time, two gods were born in the heavens (or the clouds), and these two were called Umashi-ashi-kabi-hikoji-no-kami and Ame-no-toko-tachi-no-kami. These first five deities, called collectively the Kotoamatsukami, were neither male nor female, and did not pair up to create the rest of the universe. In fact, they did nothing else at all. They hid themselves upon their creation and were never seen again, and indeed they are not mentioned at all in the rest of the mythologies. Which, as many of you will agree, is rather fortunate, as you are less likely to have to remember their names.

After the kotoamatsukami, another sexless pair was born that also hid, followed finally by five pairs of female and male goddesses. In each pair, the male was born first, then the female, and they were regarded as both siblings and couples. These pairs were U-hiji-ni and Su-hiji-ni, Tsunu-guhi and Iku-guhi, O-to-no-ji and O-to-no-be, Omo-daru and Aya-kashiko-ne, and Izanagi and Izanami. These 17 gods — the sibling pairs and the aforementioned godly layabouts — are collectively known as the Kamiyonanayo, or the seven divine generations.

The Beginnings of a Nation

Upon their creation, the last pair — Izanagi and Izanami — went on not only to create the Japanese islands but also many other kami. Interestingly, all of these were created by their reproducing, including the Japanese islands themselves. The myth generally goes as follows:

Izanagi and Izanami, standing upon the floating bridge of heaven, both made a plan together saying, “Is there not a country in the depths?”, then they took the heavenly jeweled spear. They thrust the spear down and searched, and found the blue sea. From the spear point dripped brine, which hardened and became an island. The island’s name was Onogoroshima.

The two gods then went down to the island, and they wished to become man and wife, and give birth to the country. Using Onogoroshiima as a pillar in the center of the land. The male deity (Izanagi) turned to the left, and the female deity (Isanami) turned to the right. They went around the pillar of the country and met face to face. Then the female god first said, “Wonderful, I have met a beautiful young man.”

The man replied unhappily, “I am the man. It is proper that I speak first. How can you, the woman, speak first? Things are already unsatisfactory. Let’s go around again.” Thus, the two gods met again. This time, the male god spoke first, saying “How wonderful, I have met a beautiful girl.” Thereby, the male and female gods began their union and became man and wife. At the time of birth, first came the placenta, the island of Awaji. It was unsatisfactory. This and all other islands came to be formed as the fruit of their union.

From here, the pair went on to also create many kami (who also created more kami) as well as the general population of Japan. Eventually, when one of these god-born men (whom we will be covering in just a moment) takes action, the “Age of the Gods” ended and gave way to the next one. The myths that follow are from the very beginning of this period.

Royal Origins

Royal Origins

Both the Nihon Shoki and Kojiki (and to a lesser extent the Hotsuma Tsutae) place a great deal of importance on cataloguing the imperial family including their origins and lives. These mythical accounts point to a great deal of magic use among the ruling family (or at least their court). One of the best examples of this can be found in the tale of the first emperor, Jimmu-tenno. Tenno, it deserves to be noted, is simply the word in Japanese that denotes his title, and roughly means “emperor.” Jimmu -- which directly translates to “divine might” -- is chronicled to have been a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu as well as being tangentially related to the storm god, Susanoo, though he is noted to have had mortal parents. The prevailing opinion of most magical scholars is that these two gods were likely powerful wizards and witches in their own right, and Jimmu is simply one of the best documented ancient Muggle-borns.

Whatever the case, Jimmu’s story tells of his birth in 711 B.C.E. during what later became known as the Yamato dynasty and also marks the very beginning of the “Age of Humans.” His main accomplishment involved conquering large portions of land and other neighboring clans, and unifying them under one major government or empire.2 The most famous of these conquests was at Naniwa, what is now Osaka. After his brother was killed in battle, Jimmu received a premonition that the battle could be won if approached from the other side. Once there, he and his party were met by a Yatagarasu, a now-extinct, enormous, magical bird native to southeast Asia. The bird was not only seen as a good omen, but lent its divinatory ability to the young man and allowed his clan to secure the strategically advantageous territory and gain an important foothold. From there, Jimmu was able to defeat the leader of the clan that held that particular territory and went on to Yamato where he eventually formed the beginning of the Yamato dynasty, and thus the rest of the Japanese dynasties to come. When he died 126 years later, by what is thought to be a bout of magical exhaustion, his empire ranged farther than any other single person had accomplished (and would only later be bested by emperors in the Common Era).

Religions

As has already been alluded to, Japan is home to many layers of religion that have formed over many years. While each of the following that will be discussed is a separate religion unto themselves, keep in mind that nothing exists in a vacuum and each of these also influenced each other, and were also influenced by outside sources. Indeed, Buddhism was not original to Japan and was brought over from China. However, in the following sections, I will attempt to highlight the practices that are unique to each religion, or list defining features, with special attention to how each religion influences the mythology of Japan.

Shinto

The second most prominent religion in Japan, and one of the most popular traditional religions, Shinto has a strong focus on ritual and is the religion to which many of the national shrines are dedicated. These shrines typically celebrate specific kami (or “spirits”) who govern specific aspects of life. These kami (of which there are millions) make up the entirety of the Shinto pantheon.

While this religion is only the second most popular, more than two thirds of the population participate in various Shinto practices, such as specific rituals, visiting shrines and making offerings, or participating in Shinto-derived magical practices. This religion, as we will discuss later, has a profound effect on the magic users of Japan.

Oomoto

Also known as Oomoto-kyo, the religion was founded quite late in the game (in 1892) and is a derivation of Shinto. Founded by a seer, Deguchi Nao, Oomoto also believe in a few select kami, and is considered a new revival of the ancient traditions. It is gaining popularity with present-day witches and wizards, but apart from this, does not have many defining features with regards to mythology and magical topics.

Buddhism

Finally, we have Buddhism, the most popular religion among the Japanese population. While the religion was initially brought over from China, it has also developed into its own entity in the island nation of Japan. It was first introduced by way of the Silk Road (a phenomenon which I am informed was discussed in History of Magic), and was made the official religion of Japan in 592 C.E. by one of the current ruling class, Prince Shotoku.

Since then, it has been re-introduced under many different sects or schools. In each introduction, the basic tenets remain largely the same, as was covered in History of Magic during your First Year. Its importance to mythology and magic lies in the hierarchy of gods. The first, and highest, level of divinity is occupied by buddhas, or those who have achieved nirvana and left earth. The second level are called bodhisattvas, who are similar to buddhas, but have not chosen to leave the earth. Both of these levels are believed to contain accounts of magical persons from the past who have achieved great feats (and therefore been immortalized by the religion).

Kami

During our discussion of religion, we did touch on the concept of kami, which is by far the most important to the magical history and mythology of the country. As Shinto is one of the most ancient religions from this area, it remains untainted by other countries’ lore, and therefore most accurately reflects the history and magical persons of the continent. Nowhere is this more obvious than the stories and lore behind the kami.

Kami occupy a wide range of existence. According to the official religion they are spirits, and you may become one after death; however many of these kami were once simple witches and wizards. Of course, others were creatures, others are simply imagined persons born of very good stories, and still more are combinations of the three that have developed over time. It is also pertinent to note that we have been able to confirm this via interviewing actual Japanese spirits whose personal narratives match up near perfectly with the mythological stories of kami. In this next section of the lesson, we will be discussing three very interesting and unique kami that fall into each of the three categories named earlier.

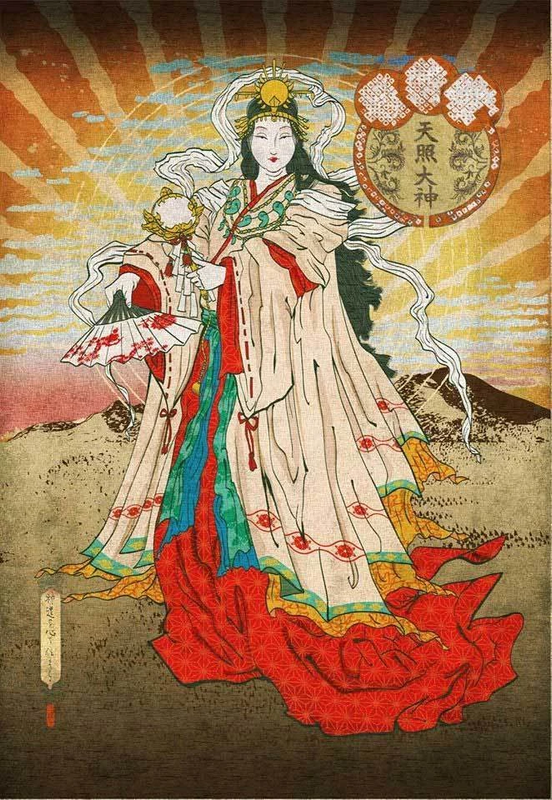

Amaterasu

Amaterasu

Our very first kami to discuss is none other than the sun goddess (and great grandmother of Emperor Jimmu) herself, Amaterasu. As one of the oldest kami, she is held in the highest regard of any other kami and was once a great witch of her time. Her achievements, as far as we can tell, include being the first dragon tamer, a powerful animagi, and possibly a renowned alchemist, perhaps perfecting the recipe for the philosopher's stone millenia before it was rediscovered and recreated.

Susanoo

Another one of the kami already mentioned in this lesson, Susanoo has been a bit of an unsolved mystery to magianthropolgists and magical scholars worldwide. It appears that Susanoo’s existence is owed to not only the actions of an ancient wizard, but also a terrifying unnamed magical sea creature, and a dash of creative local storytelling. The combination of these three components creates the mythological and spiritual persona known to many as Susanoo.

While we know, at one point, there was a human to which many of Susanoo’s deeds were attributed, who exactly he was is lost to time. Some believe him to be the actual brother of Amaterasu (as the myths claim), while others think he lived in an entirely different century (and perhaps and entirely different millenium). Whatever the case, his deeds have become so intertwined with a conflicting stories, that it is hard to discern myth from fact (and, in some cases, the beginning of one myth from the end of another). He is included in the aforementioned tales of the mythological sea creature, numerous stories attributed to assorted real persons, and accounts of various myths or legends that serve as the foundation of multiple religions

Watatsumi

Actually once a whole host of creatures (of the same species), these creatures are the basis for a number of myths or mythological persons in Japanese and general eastern mythology. These creatures greatly resemble dragons, and are thought by current magizoologists to be related to them scientifically. They are not one of the currently established breeds of dragon as they are believed to be far more reclusive and are still, as yet, only regarded as full-blown creatures by cryptozoologists, but many a magizoologist hopes to prove their existence one day.

They are believed to have a long, serpentine body (a classical “sea monster” description) as well as the ability to hibernate for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. Little else is known about them, but they are believed to have been hunted to extinction millenia ago.

In mythology, these creatures make up the body of many different figures including -- at the very minimum -- the dragon kings and many other “sea monsters.” They are often attributed with the gift of human speech, but this is thought to be either an exaggerated feature or a misinterpretation of their telepathic abilities.

Creatures

Without a doubt, you have all heard of the fearsome Kappa, discussed both in Defense Against the Dark Arts as well as Care of Magical Creatures. However, this is (by far and away) not the only unique magical creature to this area. Just as Asia is home to copious different magical (and Muggle) communities, there is quite the biodiversity in both beasts and beings.

Bakemono

A creature belonging to the same family as the goblins of Europe, these creatures are said to have migrated here about the same time as humans (in roughly 40,000 B.C.E.). Once there, their development branched significantly, resulting in a human-goblin hybrid that is especially adept in transfigurative magic. These creatures appear to have a highly codified view of right and wrong and will often bestow gifts (usually tools and artefacts to improve magical ability or specific magical skills) upon those they deem worthy.

These creatures, similar to the position of centaurs and merpeople in Europe, are viewed as deserving of “being” status, but as the various statuses of Asia are a bit less stringent, their designation is up in the air. This is further compounded by the Bakemonos’ complete disregard for upperground politics. As a side note, it should also be known that the Bakemono are our best source of information on the Jinshin, and many a gift has been translated into knowledge about these burrowing creatures.

Ho-o

A genetic relative of the phoenix, the Ho-o goes by many names in the east including the Feng-Huang, Hoo-hoo, or just Huang. This firebird is known throughout the lands there, though it is just as rare as the phoenix. Like most firebirds, the Ho-o has an affinity with flames, being able to extend its life indefinitely as long as it has access to magical fire (which is the reason for many magical fires that continuously burn at specific shrines all over the islands).

In mythology, the bird is linked with rebirth and revitalization, often included in tales of re-establishing dead rice paddies, bringing dead soldiers back to life, or engulfing the losing hero in swaths of flame only to reappear stronger and more formidable than before.

Jinshin

Jinshin

This creature is actually one of the more unique creatures to magizoology. This enormous beetle is known to cause tremors and earthquakes on the island. Typically, one Jinshin on its own does not cause these, but during the mating season, the presence of two or more combative females competing over a male can cause disturbances. Their tunnels underground span extensive networks, but have never been able to be accurately studied by humans due to their immense depth below the surface and nearness to the earth’s core. These enormous beetles strongly prefer hot, dark areas in their tunnels and will rapidly die if left too long aboveground, or even too near the surface, which does happen when older Jinshin begin to lose their bearings, occasionally resulting in surface breeches.

Interestingly, the chitin of the Jinshin is used in many local potions as a rare ingredient, with its uses ranging from love potions to defense against dark magic, making some believe that the chitin has general magic-enhancing properties.

Kirin

A form of magical equine, this creature makes unicorns pale in comparison -- though are significantly easier to track down, which may explain their low population as they are significantly easier to poach. A peaceable species, the Kirin would easily earn an X in the British magizoologists' ranking… if not for their incredibly un-boring characteristics. This multi-colored horse is highly attuned to the color spectrum, able to cloak themselves to nearly every living creature: be they those that see in infrared, ultraviolet, or simply visible light. However, when viewed, these creatures are a pure explosion of color on all spectrums.

These innocent herbivores’ pelts are used in the Contralust Potion, as well as (more notably) in the Peaceable Preparation, a commonly used potion at treaty signings and other prestigious diplomatic functions. They are most often viewed in proximity to the burials of pacifist and peaceable persons who have never committed a violent crime over the course of their life. In these cases, an equally innocent family member may attempt to collect the hair of the creature in compensation, which will be willingly given.

Raiju

Raiju

Finally we have the Raiju. Simply put -- an enormous, terrifying badger. Its hide repels spells with astonishing ease and its teeth are incredibly sharp. While it is not excessively fast, if you are not able to hit the specimen with a strong enough Stunning Spell (or a Bludgeoning Hex or other similar incantation), you will invariably be eaten by this belligerent carnivore.

Its teeth are especially potent in aggressive potions, particularly those that create offensive effects. However, they also enjoy use in Ward-Off, one of the most common (though expensive) ward maintenance potions in all of the western world.

Closing

Unfortunately, that is all the time we have for Japan today. Next week, we will move onto cover China and while there are certainly common threads, there are many differences between the two nations. If you have an interest in this specific area, I strongly suggest picking up a penfriend from Mahoutokoro, as they are more than happy to detail their mythology from a first-person perspective. Additionally, many books in our library can serve as acceptable second or third hand accounts. For now, you have an array of assignments. One quiz on general information, one essay breaking down the magical practices and social beliefs of ancient Japan, and two extra credit assignments: one a research assignment on an additional kami, and another that serves as a review N.E.W.T. assignment.

Footnotes

- It does not, however, in the Muggle community, and it has taken great pains to keep it this way, despite the intrepid efforts of one Yoshinosuke Matsumoto and his team of researchers, who have taken great pains to translate and compare the three major texts. Unbeknownst to Matsumoto, his team has a few researchers with… extraordinary talents.

- At least for a time, but that’s another story.

- In other versions, Izanagi does not protest his wife’s speaking first, but their first union is cursed by the other gods for the same reason, and their first child is born hideous and deformed (without bones). They are only able to properly conceive after they rectify the marriage ceremony and Izanami allows the man to speak first. The myth then proceeds as usual.

Original lesson written by Professor Venita Wessex

Image credits here, here, here, here, here, and here

- MYTH-601

Enroll

-

7.1 Land of the Rising Sun

Quiz -

Myth Interpretation: Izanagi

Essay -

Copious Kami

Essay -

MYTH NEWT Review: Y4

Test