Announcements

Welcome to Charms 601!

If you have any questions or comments, please do not hesitate to reach out to Professor Laurel!

Lesson 7) Charming Objects: Spellcasting Webs

Welcome to another lesson of Charms! Today’s topic is deeply linked to theoretical aspects you have already discussed in Year Two. To name the most relevant concepts, we are talking about Forms, and Deep and Shallow Object Charming. So far, all charms that you have discussed belong to the category of Shallow Object Charms, as they are not absorbed by the target material and are not interwoven. Today’s lesson will give you a small insight into spell-weaving and teach you how to implement some basic Deep Object Charms. Naturally, these contents will not enable you to enchant your own broomstick or create any elaborate magical objects: Learning to cast these spells and properly weave them into a working structure requires studies far more advanced than anything that we teach at Hogwarts. The only Forms we will be talking about are one Initiation Form, one Power Form and some basic Effect Forms. If they interest you, I would recommend looking at professional charming in more detail: Object crafters specialise in advanced Forms they learn in their apprenticeships.

Spell-weaving

Before I introduce you to actually casting Deep Object Charms, it is necessary to take a look at how those charms are applied to an object. You surely remember that there are at least three different Forms that every deeply charmed object contains: Power Form, Initiation Form, and at least one Effect Form. Naturally, those need to interact with one another to make the magical object work in the intended way. They are interrelated and permanently linked, and if one spell were to fail, the entire combination of charms would collapse. This is created by spell-weaving: the spells are combined in a way that makes them build upon one another and strengthen each other.

First of all, we will need to take a look at what we define to be ‘weaving.’ While it is a simple term and I am sure that most of you have an idea of what it means, we will discuss it briefly to make sure that everyone is on the same page. Weaving is defined as forming something by interlacing different elements into a connected whole. This is typically done with fabric or another physical material and can be done in a number of different ways by bending and winding movements. You can even take an existing structure and weave in a new strand for added detail. Naturally, magic does not behave in the same way as fabric, but we can visualise our spells much better through physically woven patterns. The result of spell-weaving is known as a spellcasting web.

Basic aspects of spell-weaving

There are multiple prerequisites that must be met for a successful spellcasting web. Using the comparison of string weaving, you can clearly envision that it is important for the strings to be sufficiently smooth. If they were frayed, it would be hard to weave them together cleanly as they may become tangled or matted. The same holds true for weaving spells. You need to ensure that they are cast very concisely. One major difference is that you cannot see your spells the same way you can see a string's texture: You will not know whether or not your spells are smooth until your weave fails. A spell becomes frayed if you cast it without applying both sufficient concentration and willpower. I will go out on a limb and say that most of your spells so far have been frayed at first, until you have mastered them. They might still work, but you will not be able to reach more elaborate results with them. This is actually the reason why I have always urged you to keep practicing your spells even after you have managed to make them work.

The next problem that needs to be considered is the stability of the woven net of spells. This directly corresponds to the order in which spells are cast. The first spell takes over the function of warp yarn, or the straight strands that begin and anchor the weave. Any additional charm is interwoven, relying on and adding pressure to the spells you have already cast. If a spell is stable, this will not cause any trouble - yet there are certain spells that are more delicate than others. If a professional enchanter decided to weave a weaker charm into the web first, they might break due to the strain caused by additional spells. Reasons for this have not been found yet, but are a matter of current research. We won’t be encountering these problems, however, as the spell-weaving that we are looking at is rather basic, only combining a limited number of spells. For a short moment, consider the number of forms and spells that are necessary to enchant a broomstick! The order in which an object is deeply charmed changes from company to company and is a closely guarded secret.

The last point that we will discuss here is the style of how an enchanter weaves spells. This is the most abstract of the ideas that we need to talk about, which is why I have brought three illustrations of various styles. Naturally, there are many other possibilities as well, and every deeply charmed object will require more than just two spells. The actual number of spells augments the number of possible variations, meaning there are an infinite amount of combinations.

You can see that while all of these designs consist of the same colours, they are inherently different. In terms of magic, this means that though you may use the same two spells, there are many ways to combine them and distribute their powers, often stressing one more or less than the other. Which weave is the best one for a spellcasting project is decided by its application. As you can see, the first one is distributed completely evenly and symmetrically. The second weave focuses more on the red and only contains bits of blue in the foreground, while the last one again has equal amounts of both colours, yet in a completely different order. To disabuse you from a common misconception, even if you might not see a strand at a certain point, the spells represented by this colour are still active. Our weave is but a visualisation aid, and not a one-on-one correspondence to the actual spells. Even if the style of weaving means that, metaphorically speaking, a red string is visible, the blue one still lies underneath. While the effect of one spell is stronger, this does not change the fact that both of them are active and interact with one another. The positioning of the strings of magic can be altered for various reasons. It may change the handling, aerodynamics, ergonomics, transition, or general applicability of the object. For further details, I will need to point you towards professional charmers though - it is not my area of expertise and is unique to every crafter or brand.

Multi-dimensional spell-weaving and its applications

While we have only considered two-dimensional spellcasting webs so far, most castings are much more complicated. The main application of spellcasting webs are enchantments of any kind, like Deep Object Charms. We already mentioned that there are at least three different forms contained in any deeply charmed object, and most of them include more than one Effect Form. Even if only one Effect Form is in place, remember that a Form includes various spells. It is not just the number of Forms that influence the number of magical strands, it is in fact a representation of the number of spells that is used to create the desired effect.

As soon as you begin to work with many multiples of charms, the art of weaving them into a coherent web becomes more and more complex. As you can see with this representation of a weaving pattern for six different strands, it is hard to actually visualise the exact position of every strand of magic in there. Yet this is required to actually cast a working Deep Object Charm. The image I just showed you is still a rather simple one, as it only contains six different strands that are all arranged symmetrically. Take a look at this picture, and try to remember every detail. Then close your eyes - no cheating! - and try to remember the details. Which colours are the vertical strands and which ones are horizontal? What is the exact pattern, do you remember the details? Taking the green strand only, which four different variants do we have, and in which order? Such an arrangement may look rather simple at a first glance, but you mustn’t forget that an enchanter needs to keep all of this information in mind.

Both the stability of the woven spells and the style of weaving them are as important for the effectivity of the magical object as the actual choice of spells. Take a look at broomsticks, for example. I am sure that you are all aware of different models and the strengths and weaknesses of different manufacturers. To create a new broomstick, a lot of research is required: Both spell-crafters and enchanters experiment with different spells. While the forms used are mainly the same, the specific spells that are used can be varied - and so can the way in which they are woven together. Once a team has succeeded in creating a working broomstick, their job isn’t finished, however. While the first broom of the Cleansweep series was released in 1926, newer models of the series are still being produced to this very day. Yet the spellwork has not completely changed for each new model: Most variations merely change the way the spells are interwoven. For example, featuring the Acceleration Charm more prominently would definitely increase a broomstick’s pick-up, yet this would simultaneously mean that other features would play a less important role. The actual weaving styles are a closely guarded secret and are never revealed, as is the actual choice of spells that are used. It is widely believed that the superiority of Firebolt broomsticks when they were first released was mainly due to an ingenious new weaving technique - yet this rumour was never confirmed nor denied.

Enhancing spellcasting webs

Now that we have discussed the theoretical aspects of what exactly a spellcasting web looks like, we need to discuss two more aspects: How exactly do you ‘weave’ spells, and how do you add further spellwork to an already existing spellcasting web? To do this, I’ll quickly remind you of the keywords we discussed earlier today when talking about basic aspects: smoothness, stability, and style. Those three attributes are essential when planning a spellcasting web. So far, I have discussed why these are necessary; now we will deal with how to put them into action.

First of all, you need to make your spells smooth. When a spell is accompanied by a visible beam of light, you can assess its smoothness rather easily. Yet how do you force your spell to take such a form? This is in fact a purely mental discipline. While concentration directs your magic, willpower shapes it. You may have already experienced that ‘sloppy’ spellcasting is less precise than when you actually take the time and pay attention to what you are doing. While spellcasting information always gives you some kind of guide as to the amount of willpower that you need, you will have certainly realised that it is not a measurable quantity. ‘Moderate willpower,’ for example, covers a relatively wide range of application.

This scheme illustrates the importance of finding the exact amount of willpower needed to make a spell work. Each of the three pictures shows a working spell (purple) and the environment (green). Research has proven that magic pertaining to a spell and ambient magic react similar to non-magical osmosis. The spell you cast is contained in a beam which behaves like a semipermeable membrane (i.e. allows only certain particles to pass through), which can (and will) always come into contact with ambient magic. Particles might be exchanged, depending on the ‘concentration’ or saturation of magic. If too much willpower is applied, as depicted on the right, parts of the spell will radiate to the environment to balance the level of magic. If not enough willpower is applied, ambient magic will pour in the spell’s beam and hence diffuse its effect. Only in a state of equilibrium, little exchange will take place. This is actually what we are aiming for: a smooth spell with little to no exchange of magic. While it is necessary for you to apply willpower as specified in the spell details, sufficient practice will lead to a self-regulation of your spellcasting. Spells want to be cast smoothly. When you cast a spell, you can intentionally vary the amount of willpower you use. From there, your magic and subconscious will adjust the width of your spell accordingly to create the smoothest possible spell. While this process is by no means perfect, as it cannot adjust to major discrepancies in willpower, practicing your spells will greatly improve it.

Professional charmers will need to deal with even more aspects, namely stability and style of the weave. This is something that you will not need to worry about in this class, as we will not be dealing with sufficiently complex enchantments. The spells that you will weave are relatively stable and should not cause any problems. As for the style, the enchantments I will be having you attempt exhibit only minimal differences between varied styles, so any weave should do. Obviously, professional enchanters need to account for these miniscule differences, but amateur casters such as yourselves do not need to be bothered.

The actual weaving process begins with the very first spell that you cast. It is essential that you have a plan for which spells you will use, in which order you will cast them, and how you will weave them together. You will only be working with three spells: one spell which belongs to the Power Form, one of the Initiation Form, and one of the Effect Form. Because of this, I will be using pictures to illustrate weaving only three spells.

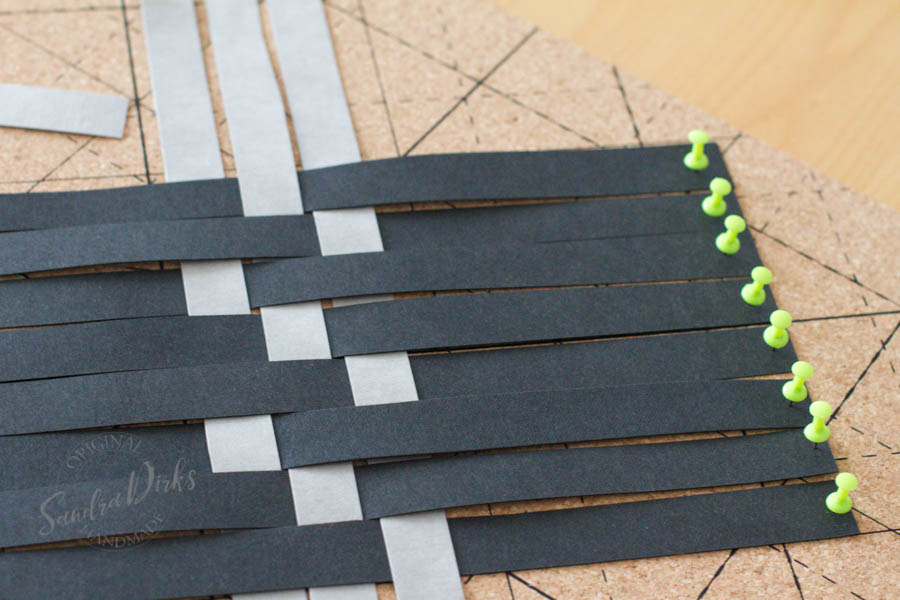

The first spell is the easiest to cast. It is important that you pay attention to making the layers of the spell parallel to one another, so that they won’t overlap. Again, we are using muggle crafts to illustrate this process.

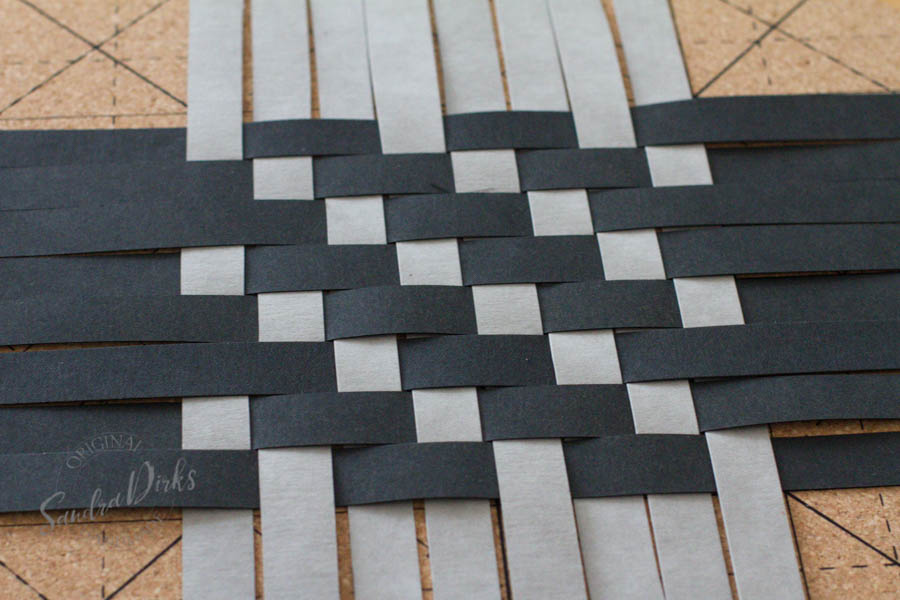

While the layers look like multiple versions of one and the same spell in our visualisation, you only cast the spell once, picturing it in a parallel structure. There is no difference in the way you are casting these spells, except for the fact that you need to concentrate on their exact position and keep the weaving style firmly locked in your mind. As soon as you have layered your object with the first spell, the second one is added according to your pattern. As depicted above, the pattern we will use is a symmetric one.

For casting the second spell, this means the following: you still need to concentrate on the first strands of magic that you weaved around your object, then you need to direct your magic to make the second strands fit in between the first ones. It is sufficient if you focus on the defining part of the pattern, but some of you may find it easier to picture the entire spellcasting web as a whole. There is no ultimate reason to pick either of these methods, it is a matter of personal preference and completely up to you. While we are not weaving these spells physically, you may be wondering what we’re going to do with the “edges” that are forming. If you will sit tight for just a little longer, we will discuss them shortly.

Following usual weaving procedures, our two strands are the Power Form (black) and the Initiation form (grey). As a last step, you are required to add the Effect Form, which is depicted by the white strand.

This is the point where visualisation becomes most complex - yet keep in mind that we are still only working with three different spells! Again, take your time to track the strand, to guarantee that you comprehend its movements. It is weaving in and out both grey and black strands, completely symmetrically. Again, weaving in this spell requires an immense amount of concentration: You will need to keep both of your earlier spells in mind and direct your magic to follow the pattern just as you desire.

With this information in mind, you ought to be able to answer the questions I asked earlier by yourself: You weave spells by using an immense amount of concentration and planning your casting in advance. Adding further spellwork to an existing spellcasting web is essentially possible, for so long as you know which spells have been interwoven already and in which way.

Edges and wrapping

As I promised you, we still need to discuss how you cover an object with the spellcasting webs that you now theoretically know how to cast. Two questions come to mind: How do you make them sink into the object, so that it isn't just the surface area that is shallowly charmed;and how do you work with the edges of the spells? These two questions correlate, which is why I will discuss them both at once.

To start with the edges of your web, the explanation will not be too satisfying, I know. To make it simple: magic. It is not fully understood how exactly it works with the webs and why your spells won't unravel starting from the edges - the standing theory is that it is a matter of concentration. As you shape your magic into the form of strings and weave them, you also want to ensure it does not unravel, so you will not need to start again. Your concentration acknowledges that fact, so to speak, and works accordingly. Yet this is the point where our visualisation of non-magical weaving fails completely. It is impossible to weave any kind of fabric without dealing with the edges - yet this is exactly how spellcasting webs work. The only thing left to discuss is how to apply these webs to the object that you are aiming to enchant.

You surely remember from all the way back in Year Two that the unique attribute of Deep Object Charms is that they are not simply superficial, but rather absorbed into the material. It is this absorption process that makes them much more permanent than Shallow Object Charms. We need to consider two aspects for this: How to surround the object with the web, and how to make the charms sink into the material to finish the process of enchanting.

You basically weave a sheet, then you need to wrap it around your object so that the entire surface area is covered. Naturally, the difficulty of this task is influenced by the complexity of the object: the more intricate an object is, the harder it will be to wrap with your woven sheet of magic. This process is somewhat similar to wrapping Christmas presents, yet we have a minor advantage: Magic is bendable and will adjust itself to fit our surface area to a certain degree. It is not necessary to shape our web so that it will fit the object exactly, as it will stretch and small unnecessary extra parts will fade away.

Making the charms sink into the material to create a deeply enchanted object will require a bit more thought. In Year Two, you learned that there are different types of materials that can be enchanted and that all of them have different attributes. To jog your memory, we talked about synthetic, mundane, transitional, and magical materials. An even further distinction exists for the last of these: magical materials are categorised as either naturally or artificially magical. Year Two discussed these definitions in depth, so please go back to your notes in case you do not remember all the details anymore. The most important point for our discussion here is the fact that each of these materials contains a certain level of inherent magic. It is this inherent magic that is the final pitfall for enchanting objects. This is where willpower comes into play: To ensure that the enchantment takes hold, you need to exert sufficient willpower to overpower the object’s inherent magic. The difficulty of this task depends on the material you want to enchant, as you can surely guess. While synthetic materials contain little to no inherent magic and hence do not pose many difficulties when enchanting them, naturally magical materials present a big challenge, especially for inexperienced enchanters. As you meld the enchantment with the object, the natural magic of the material may reject it such that your web cannot take hold. Yet it is the natural magic that enables the enchantment, when successfully absorbed, to last significantly longer, making naturally magical materials the most sought after for object crafting.

That’s it for today’s lesson. Next week, we will briefly discuss some more theory before starting with a bit of practical application. I am sure that you are all looking forward to creating your first enchantments! For next week, I want you to do a compulsory quiz and essay. Until then!

Professor Cassandra Virneburg

- CHRM-OWL

Enroll