Lesson 4) Gardiner and the Brothers Baldric

As is quickly becoming a habit, Professor Wessex is nowhere to be seen in the busy period before class starts this morning. The enchanted quill scratches away intermittently at the front of the room. One student, chatting and laughing with her friends, pops in some Drooble’s Best Blowing Gum and stashing the rest in her pocket.

One minute before class starts, Professor Wessex makes her usual entrance and, after consulting the parchment, swiftly draws her wand and performs two precise movements. The student in question blinks once before licking her lips with a puzzled look, as if surprised to suddenly find that the sweet she had been enjoying has suddenly disappeared. The pocketed candies zoom towards the desk where they are secreted away in a drawer. Without further ceremony, the prim professor slides her wand back into her sleeve and begins the lesson as if there had been no interruption, though you get the distinct impression that House Points were just lost.

Hello again, Fifth Years. Over the last few weeks, most of you have proven yourselves adequately adept at understanding the foundation of magical hieroglyphs. This is extremely fortunate, as the level of difficulty is rising significantly. Today marks your introduction to the practical side of enchanted hieroglyphic spells, with particular emphasis on the signs used in said spells. However, before we get into all of that, we will be taking a few moments to discuss our next grammatical puzzle piece to assist us in both decoding hieroglyphic spells and correctly fashioning our own.

Word Order

While there are many things about ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, particularly when applied to magic, that can be easily confusing, word order is not one of these things. Despite the many changes that the script went through over a span of roughly 3,300 years, word order remained largely the same. The general order goes as follows:

- Verb

- Subject

- Object

- Adverb (or adverbial phrase)

Therefore, if we were to rewrite the sentence “Salazar enchanted the chamber secretly.” in this format, it would become “Enchanted Salazar chamber secretly.” (remember that articles are not present in hieroglyphics). One important thing to keep in mind for the rest of the lesson, however, is that these rules apply stringently only to the phonetic level of spells. The magical level was much more free-form, though this word order certainly still did influence the magical/ideographic level of spells from time to time.

A Brief Note on Gardiner and Categories

With that sorted, it's now time to move one step closer to the main event of the lesson. As was discussed in your Fourth Year, in order to keep all of the symbols straight, Egyptian hieroglyphics are organized into a number of categories created by Alan Gardiner. As we discussed last year, Gardiner was indeed a Muggle. However, his insights have proven useful for the foundation of our knowledge. These categories serve as a way of standardizing conversations about the symbols; nothing would get done if witches and wizards had to describe each symbol. For example, simply referring to a glyph as “B4” (indicating that it is the fourth symbol in category “B. Woman and Her Occupations”) requires far less time than describing it as "a woman sitting with one arm raised and with three short, lines underneath that end in small circles”. Moreover, not only does the category save time, but it also avoids confusion and the potential for misunderstanding, as one person may describe the symbol in a different way than another and there are many, many variants.

That said, over the course of the year, there will inevitably be times where you will need to consult said list despite the fact that you have not been taught all of the glyphs on the list in class. There is just not enough time to go over each glyph in every category in detail, discussing what it means in addition to theory, magical applications, and grammar. Moreover, for the novice or average ancient script enthusiast, there is not much need for you to have all of these symbols memorized due to the fact that those who have come before you have compiled excellent lists for your reference.

Therefore, for the remainder of the year-- and perhaps longer, depending on your path and personal preferences-- you will be provided with a complete1 version of Gardiner’s Sign List. More of a pocket-sized guide than a book, you will need to bring it to class with you each week, as you will find it instrumental when examining and attempting to pick apart the long sequences of Egyptian hieroglyphic spells. Take a moment to flip through the pages of the booklet and familiarize yourself with it as I discuss its contents with you.

In the front matter, we see the table of contents lists 29 categories, the main ones being the 26 from A to Z (excepting “J” and including “Aa”). The last three categories -- “Tall Narrow Signs”, “Low Broad Signs” and “Low Narrow Signs” -- do not have their own letter designations. These could be considered “re-classifications” as all the signs in these unlettered categories are categorized elsewhere with the traditional lettered groups. However, you will quickly find that the three unlettered categories, in some ways, are the most useful categories; if you encounter a sign whose category you do not know, you can search one of these three groups in order to find its designation (and therefore its phonetic or magical meaning).

Animal Signs and Why They Exist

Another thing I would like to draw your attention to is the number and variety of glyphs relating to animals. If we look only at the category headings, we will notice that seven of the twenty-six major categories are related to animals. These categories are very specific; for example, there are two separate categories for mammal-related glyphs. There are many factors that contribute to this prevalence of animal signs, including the Egyptians’ religious beliefs, their variety of contact with other cultures, their use of animals for numerous tasks in the empire, animals’ use in many magical practices, and the fact that magic was simply another part of life in ancient Egypt. Therefore glyphs of magical animals are present alongside mundane animals. While we will not be able to discuss all the reasons at length, I have invited a guest to talk to you about one of them.

Give Professor Anne, your Care of Magical Creatures instructor, a warm welcome. She will be taking time today not only to demonstrate how something we perceive to be a single object can be broken up into many different parts with various uses, (and therefore why there may be more than one glyph related to the same animal) but also give brief examples illuminating the importance of parts of animals in the ancient Egyptian religion.

Guest Lecture

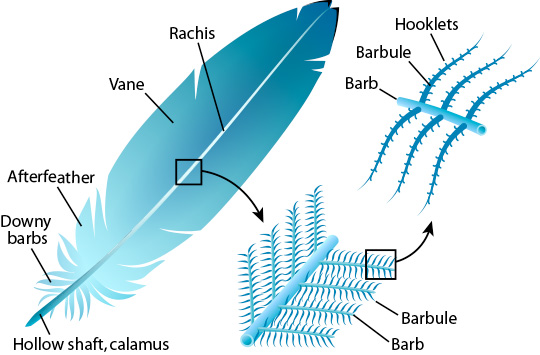

Good day everyone! Thank you to Professor Wessex for inviting me to speak to you for a bit today. Now, I understand you have been discussing different animal-based hieroglyphics. You might have noticed that many of these hieroglyphics have to do with birds and parts of birds. While birds were an incredibly important part of Egyptian society, one of the most symbolic parts of birds are their feathers. Let’s first look at the different parts of the feather.

The calamus is the main portion of the feather, or the shaft of the feather. It is what allows the feather to be attached to a bird. The downy barbs and afterfeather are the light, fluffy down of the feather. The afterfeather will be slightly stiffer than the downy barbs. The rachis is connected to the calamus. It is the spine of the feather, so to speak: it connects all of the parts of the feather together. Th e vane is the main body of the feather, which consists of barbs, barbules, and hooklets. The barbs are the lines that are connected to the rachis. On the barbs are barbules, which meet perpendicular with the barbs. On the barbules, there are hooklets, which are perpendicular to the barbule and parallel to the barb. The hooklets connect each barb to the next, which ties the feather together and gives it the solid appearance you see.

e vane is the main body of the feather, which consists of barbs, barbules, and hooklets. The barbs are the lines that are connected to the rachis. On the barbs are barbules, which meet perpendicular with the barbs. On the barbules, there are hooklets, which are perpendicular to the barbule and parallel to the barb. The hooklets connect each barb to the next, which ties the feather together and gives it the solid appearance you see.

While all of this seems unimportant, it is essential to how the feather is used. Presently, we use feathers as quills: our writing implements. When you are selecting a quill, which of the following sets of feathers would you pick a quill from: Set A or Set B?

Set A Set B

As you can see, the feathers in Set A are missing parts of the vane, causing them to have holes. While the feathers are from a breed of bird that naturally has that gap, they are not desirable for quills because they look incomplete. The feathers of Set B are not missing parts, meaning it is a complete feather. Complete feathers are better used for quills because they have a more pleasing appearance.

You are probably asking yourself, ‘What does all of this have to do with ancient runes and the Egyptian hieroglyphics?’ The feather used in hieroglyphics is meant to represent an ostrich feather. If you look at the hieroglyph, which I have provided below for you, you will notice it has a curved tip, almost as if the feather is tipping forward. This represents the tip of an ostrich feather, which is heavier than the rest of the feather, thus bending under its weight.

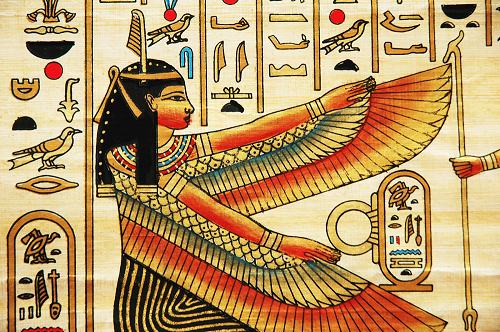

Feathers are seen so often in hieroglyphics because they were used to represent two different Egyptian gods, as well as having ideographic and magical significance, as many hieroglyphs do. The first is the god of air, Shu. Shu is also the father of the goddess of the sky, Nut, who is frequently represented as a woman with a vase of water atop her head, and the god of the earth, Geb, who is often represented with a goose. In Egyptian art, Shu is shown wearing feathers in his hair, or sometimes completely covered in feathers to represent the air that surrounds him. The second god is Ma’at, who is the goddess of truth and wisdom. T![]() his was the more frequent representation of the feather, as a feather alone was her emblem. She is always shown wearing an ostrich feather in her hair.

his was the more frequent representation of the feather, as a feather alone was her emblem. She is always shown wearing an ostrich feather in her hair.

I do hope that helped you see some connections between Care of Magical Creatures and Ancient Runes, and how animals and their parts are not only significant for their use in potions, but for their use in ancient languages and cultures. Thank you again to Professor Wessex for allowing me to pop in today. I will see you all around the castle, or in class for those that are my students!

Professor Wessex claps softly, leading the group in a round of respectful applause, sparing a stern look for anyone that does not join in immediately. Thank you for that illuminating example, Professor Anne. I am sure students appreciate the benefit of your lecture.

As your professor has demonstrated, even something as simple as a feather holds a wealth of meaning. This is one of the main reasons why animals feature so prominently in your list of glyphs. And, of course, as Professor Anne mentioned, and as you have covered in your Mythology and Ancient Studies classes, the Egyptian pantheons are full of anthropomorphic deities and animal parts as symbols.

As your professor has demonstrated, even something as simple as a feather holds a wealth of meaning. This is one of the main reasons why animals feature so prominently in your list of glyphs. And, of course, as Professor Anne mentioned, and as you have covered in your Mythology and Ancient Studies classes, the Egyptian pantheons are full of anthropomorphic deities and animal parts as symbols.

There are certainly other reasons as well. It is often the case that each part of the animal has a different significance, for example, the stomach and claws of a creature might represent something entirely different simply because they symbolize different things in ancient Egyptian culture. This is especially true for animals associated with magic. Animals that are inherently magical, are used in potions, or were simply associated with magic (or heka) in ancient Egypt are prominently included and part of the reason for the sheer number of animal glyphs, which brings us to our last topic for today.

Cultural Contrast The Baldric Brothers and Gardiner’s List: A Magical Addendum

As I said, we in the wizarding world use Gardiner’s categories just as Muggles do. However, in some areas these categories are a bit lacking. Because of Gardiner’s lack of magical knowledge, a fair portion of information relative to curse-breaking, magiarchaeogloy and magianthropology was obviously overlooked. That is not to say that it has not been studied, of course, but a clear, concise list of the magical meanings and applications of hieroglyphics was sorely needed. Many individuals, particularly over the last hundred years, have attempted to compile a list comparable to Gardiner’s, notably Magical Hieroglyphs and Logograms and Spellman’s Syllabary. However for numerous reasons these attempts have been unsuccessful. The most notable of these reasons is the fact that those in the curse-breaking business often have very short careers and do not always collaborate as beneficially as they should. Very abbreviated guides do exist, mostly detailing cultural information and a list of trends in hieroglyphic spell work, but none had come remotely close to being as practical as Gardiner’s Sign List, until recently.

In 2011, a pair of brothers graduated from Hogwarts’ own halls and, over the years with the help of editors from Merge Books, published Gardiner’s List: A Magical Addendum. While the work is short, it was quickly lauded as one of the most thorough and accurate guides to hieroglyphic magic. What it lacks in length, it makes up for in practicality and ease of use. The two Hufflepuff brothers -- a curse-breaker and a magiarchaeologist -- used information directly from their own meticulous field notes as well as interviews from colleagues in the field that were pieced together to give a hands-on guide. Notes range from glyphs commonly used together, the magical uses and meanings, and the brothers’ various anecdotes and in-the-field experiences involving the glyphs.

This title is particularly useful to us, as we will soon delve into picking apart actual hieroglyphic spells, and, as I will explain in the next lesson, these additional magical meanings will be essential to your understanding of the spells’ mechanics. You will find the title in the library if you were negligent enough to not obtain a copy, as your supply list this year indicated, but be advised that the book is rapidly becoming a must-have for anyone who is serious about ancient Egyptian magic.

For example, if we saw a snippet of a spell that looked like this:2

![]()

![]()

![]()

And if we had the Magical Addendum handy, we would notice the presence of three main glyphs: C12, T31 and O35, respectively. Even if we were not immediately able to identify their category, we would be able to use the last three unlettered categories as a reference to look them up.3 We would note C12, if part of the magical layer of the spell, indicates concealment, T31 indicates the presence of an equivalent to a Sharpening Charm and O35, which is the glyph that animates inanimate objects. With this information, we might conclude that somewhere, sharp objects had been hidden -- knives, spears, staves, daggers, etc. -- that had been enchanted to move in a particular way. Now, this doesn’t answer all of our questions, but it is certainly a start and would give us an idea of which other glyphs may be pertinent to the magical level of the spell.

Closing

Your homework will include a few practice spells -- nowhere near as long as an actual ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic spell -- for you to decipher in order to warm up and accustom yourselves to using the Magical Addendum efficiently. Additionally, there will be an assignment to ease you into using the category system from Gardiner’s List. It is expected that you will use the book in order to help you with this assignment, as it is only practice. Last, in terms of required assignments, there will be a quiz on the general information presented in the lesson.

Footnotes:

- As complete as you will need, anyway. A truly complete list would be too overwhelming and wholly unnecessary due to the number of variants.

- Note that it is incredibly unlikely that a hieroglyphic spell would cluster all of its magical glyphs together like this. Since the spells have a phonetic level as well, the spells do actually have to make sense phonetically and make words, therefore dictating the order of the glyphs. Moreover, there may be twenty mundane glyphs in between two magical ones. However, for the purpose of acclimating you to hieroglyphic spells, we will not immediately be starting with spells that are 500 glyphs long with twelve enchanted glyphs sprinkled in for you to pick out.

- The latter two, for example, might be found in the category titled “Low Broad Signs”.

Original lesson written by Professor Venita Wessex

- ANCR-401

Enroll

-

Name That Category

Quiz -

Decipher the Spells

Essay -

5.4 Gardiner and Glyphs

Quiz -

Review YF Transcriptions (EC)

Essay